Not Everything Needs To Be Said

Lessons from seeing Stephen Colbert, Ocean Vuong and Shakespeare this week. Plus, a moving interview and playlist.

Before the cameras start rolling on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, Colbert does a Q&A with the audience. Last month, when I attended the show for the first time, my friend and I came up with a question that was relevant to both of us. As a journalist who lost a parent young, I wanted to tell Colbert that he’s been incredibly influential in both my career and my understanding of grief (he lost his dad and two brothers in a plane crash when he was 10). I planned to share this context followed by the question: “how does your grief inform how you process and make light of such difficult news on a daily basis?” The pent up energy from all the years I was too shy to raise my hand as a kid were now funnelled into my adult body, as I shot my hand up eagerly. He took a handful of questions and ours was not one of them.

But this week, I had a second chance. I attended the Colbert show again, and raised my hand with the same question. “Last one,” he said, as he gestured to me. The tone of the questions this time around was lighter and each question came without context, so I followed suit, skipping my own experience and admiration for Colbert and cutting straight to the question. I was nervous and stumbled over my words but he understood. Pausing to consider the question, he then looked up at me and held eye contact as he answered. It was the most thoughtful and lengthy answer yet, and I could sense the audience becoming more still and attentive.

Unfortunately I was so nervous over maintaining his gaze that I wasn’t actively listening. (I was thinking, “Colbert is looking at me, look engaged. Why is my face trembling? Does my expression look weird? Omg. Omg.”). I think he described how he loves the Irish because they know how to both laugh and cry, and to not turn away from pain and difficulty. He said something along the lines of how grief hurts so much because of how deeply we loved. His own grief enables him to handle the news because he has a deep love for his country. He knows how to not turn away from the things he loves, no matter how painful or hard they may be to hold.

I never got to tell Colbert the context of my question; to share how influential he’s been in my own life; that I, too, understood grief. I thought I’d feel frustrated by my own withholding, but instead I felt my heart swell. When he chose me to ask my question, he referred to me as young lady, and given all the topics that preceded my question were light (think: The Hobbit), it made my question about grief seem more personal. I sensed that he knew I was speaking from a place of understanding—that I knew grief—by the way he thoughtfully paused to contemplate his answer, and then held my gaze for the duration of the answer. His face was both serious and tender, almost like he was advising a child. What his body language and facial expression emoted was empathy. I left feeling content, convinced he had received my message without me actually articulating it.

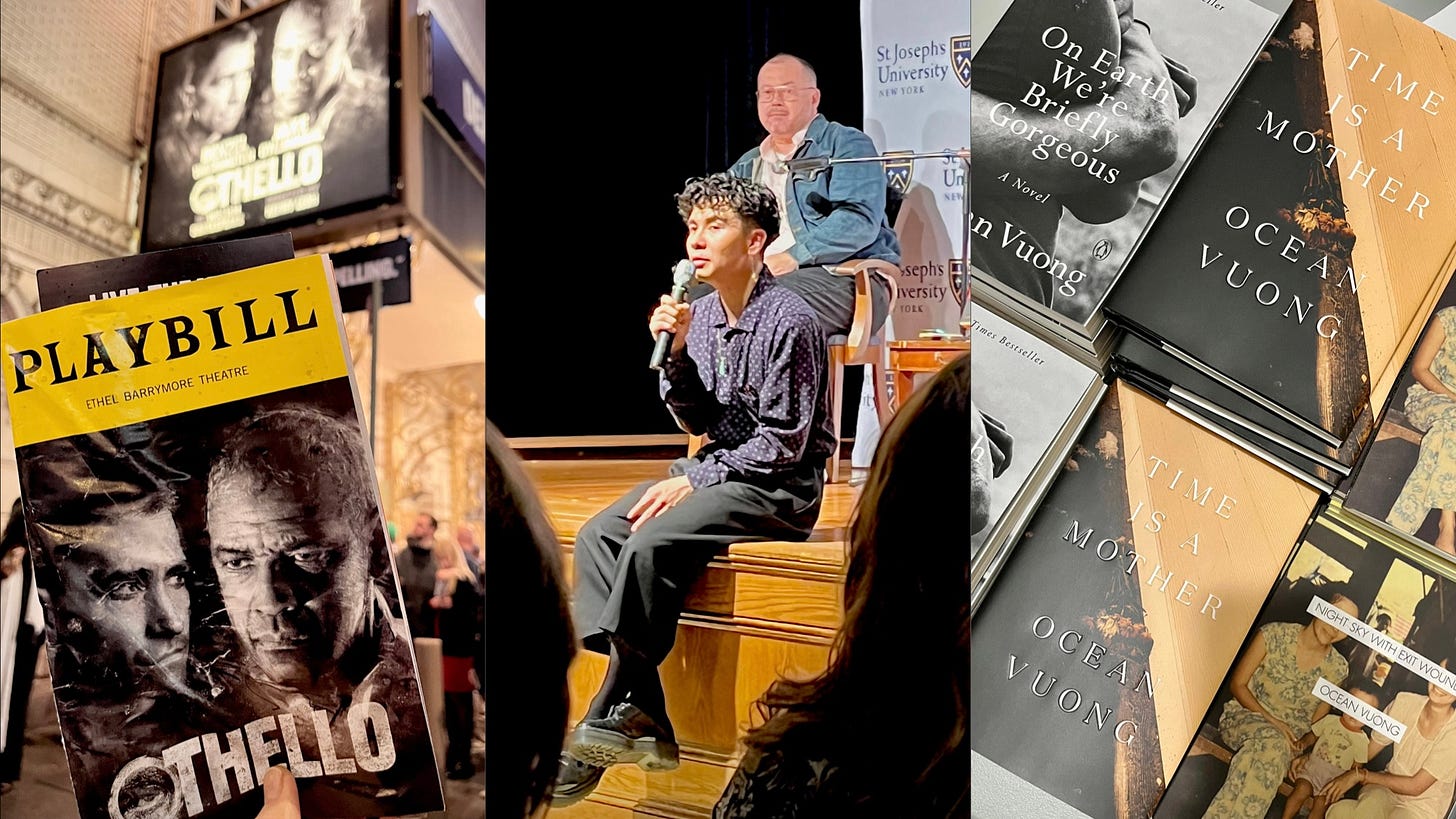

If anyone understands how much can be communicated in the absence of words, it’s Ocean Vuong. His novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was written as a letter to his illiterate mom, who migrated from Vietnam to the U.S. with him when he was two. A couple nights after the Colbert show, I attended the launch of Vuong’s new book The Emperor Of Gladness, where he was interviewed by another author I admire, Alexander Chee. When asked why Vuong wrote his new novel in third person, rather than the first person POV of his first novel, the author said he wanted readers to learn about the characters at the same time as the characters learn about each other. He described fiction’s default third person POV as judgmental, a consequence of our culture’s proclivity for people-watching. Describing everything about a character isn’t necessary, he said, “We don’t have to know everything.”

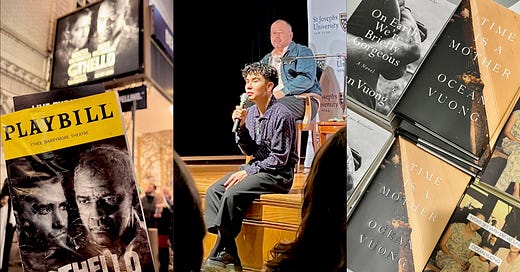

In the literary tradition, the audience expects to be let in on everything about a character and doesn’t take well to ambiguity. It’s why watching Shakespeare can be so frustrating. The playwright lays out the inner world of his characters—Iago in Othello, for example—but we might not be able to understand the sentences used to communicate them. I’ve never studied Shakespeare so I was admittedly a bit lost at the Broadway production of Othello this Tuesday. Thankfully, my companion had given me a synopsis beforehand so I knew what was happening, but I missed the nuances due to my Shakespearean illiteracy.

Did I enjoy the play any less because I didn’t understand the characters as much as I would if I was fluent in Shakespearean English? I don’t think so. At a certain point, I surrendered to my inability to understand everything, and redirected my attention on communication channels beyond words—tone, cadence, volume, facial expression and body language.

We live in a culture where we over-explain and feel insufficient when we don’t understand everything. The answer to every question is at our fingertips with a quick google search. Every thought is spoken aloud; every feeling purged; every part of ourselves made visible. There is little room for mystery and ambiguity, or for the possibility that we can still understand and connect with one another in the absence of words. So much is said without being said. And no matter how much is said, we can still never know everything.

Best,

Anna

Reading 📖

🍽 The most disturbing but important investigate reporting I’ve read in a while, on the starving of incarcerated people with mental illness.

🎲 I’m not the only one learning mahjong and loving what it does to my brain.

“I think of this time of year as one of unclenching, of letting go of that coiled, withholding winter self and opening up to spring. The unclenching, I am now thinking, can sometimes be challenging. Deliberately moving from a familiar place to an unfamiliar one isn’t without its discomforts. When a chick is ready to hatch, it develops an egg tooth, a sharp little structure on its beak that it uses to peck its way out of the egg. How incredible! How do we grow our own egg teeth, generate our own tools to crack our own shells, escape our too-tight enclosures and emerge into the light?” -Melissa Kirsch

👦 What parents of boys should know.

💭 When forgetting is good.

🔮 A psychic and a skeptic walk into a vortex.

👅 How did our taste buds get so spoiled?

🍔 The chef’s love-hate relationship with your favorite burger.

Watching 📺

From the Colbert show to Othello to Focus Art Fair—this week was filled with inspiration. While television and film and can be inspiring too, there’s nothing like a live performance or seeing art in person. My brain was most stretched this week at the Ocean Vuong book launch, so I’m sharing some wisdom from his conversation with Alexander Chee here.

“We write novels to give voice to people within systems or trying to survive them,” says Alexander Chee. Ocean Vuong responds, “We love stories of people who break out of systems, but most people can’t. I’m interested in the people who don’t get out. The beauty and power is in how we innovate within that system.”

The rest of the following are quotes from Vuong (some are paraphrased or might not be exact, I was frantically transcribing on my phone!).

“I refuse to believe a static life is a doomed one.”

“You’re at a fancy restaurant and they bring you all this fancy food and they say, ‘you don’t have to pay for it because it’s been paid for by your family.’ Would you not suck everything down to the bone? I owe it to my family to follow the questions down to the bone because the price has already been paid, many of them are already gone. [Writing] is not the easiest thing but it’s still a privilege.”

“The novel is both a container and genre at once. In that way I think the novel is the bottom, [audience bursts into laughter] it makes room for pleasure and it denies nobody.”

“We owe it to ourselves to look at the world deeply. Writing is an architecture, strategy, enactment but 90% of the work is about observing and seeing the world as an inexhaustible place of meaning. I can’t turn away from humanity as a writer because I signed up for all of it.”

“People ask how I can be so vulnerable but I don’t see it as labor, I see it as a privilege. I come from people who never got to write it down.

“The softness of my hand was my mother’s point of pride. Her goal was to keep my hands soft,” says Vuong, explaining how his relatives’ hands were hardened by labor. “She would point to other relatives ‘look at his hands, I’ve afforded him the luxury of reading and writing.’”

“This culture is a ricochet of ego.”

“Writers of color are not seen as creators but anthropological bridges, recorders of people of color’s plight to communicate to others to understand.”

“We are so lucky we get to be late to the archive. Baldwin didn’t have Baldwin, Morrison didn’t have Morrison, Alexander Chee didn’t have Alexander Chee.”

Listening 🎧

This interview might be Ocean Vuong’s most powerful yet. I won’t spoil it for you but he confesses something he’s ashamed to admit from his adolescence, a moment that arguably provided the moral imperative for him to become a writer.

“I didn’t become an author to have a photo in the back of a book. Writing became a medium for me to try to understand what goodness is,” says Vuong. “My first [writing] class, the syllabus was Baldwin, Annie Dillard, Foucault. And I realized writing was not writing a respectable email to get a job. It was a medium of understanding suffering. That’s when it changed.”

Vuong also talks about caregiving, a role that inspired a character in his new novel. “[Caregiving] certainly requires endurance, because you are in a heightened place of selflessness and giving with no determinate end. It’s sad, because it should be what is possible without illness—giving your loved one your best self.”

Here’s a playlist of songs Vuong listened to while writing The Emperor of Gladness.

Snacking 🍌

There was lots of eating out this week. I had two very different Korean eats—one was an elaborate hot pot feast inspired by Korean hot springs at Oncheon, the other was three interpretations of ssam (the Korean dish of handheld lettuce wraps filled with rice, meat and sides) by SOPO chef Dennis Hong at Focus Art Fair. I’ve recommended them before but SOPO is my go-to for a quick delicious, nourishing Korean meal in Midtown. I also ate at Central Park Boathouse, overlooking the lake—a touristy experience that is actually worth it. Whenever fish cakes are on the menu, I order them, because they’re always different at every restaurant. The jumbo ones here were generous with the crab and leaned creamy, a refreshing pre-Broadway dinner.