Meditations On Grief

10 years without mom. Plus, processing grief through art and laughter, and comforting nostalgic Toronto eats.

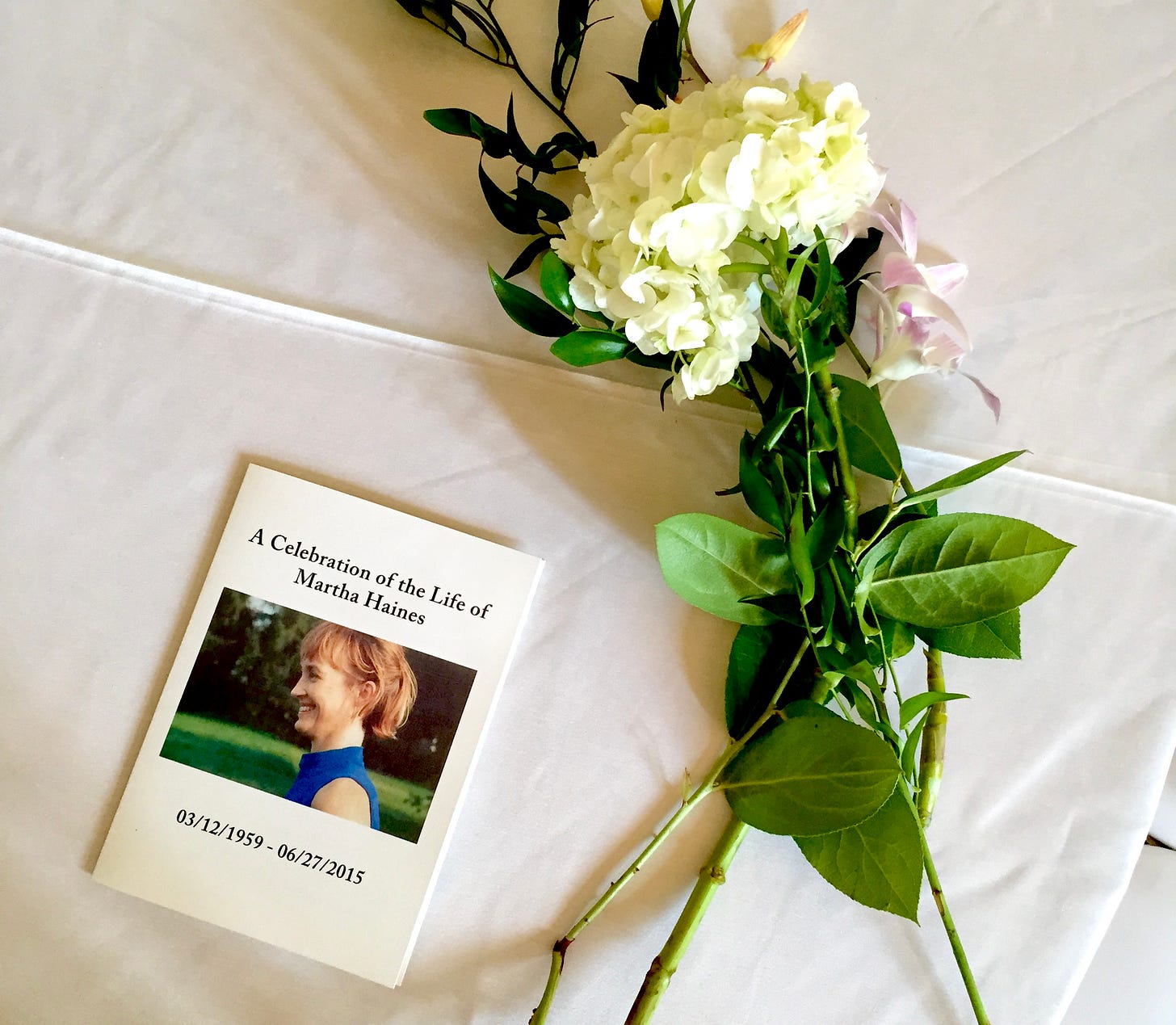

Please forgive the late Sunday’s Best, (it’s Canada Day long weekend so I’m pretending today is Sunday), and the hiatus, I’ve been on the road. With the ten-year anniversary of my mom’s death last week, I’ve been thinking about this edition for a while. If reading about grief is not for you, please scroll down to the recommendations (and if those are too heavy too, skip this one entirely). 💜

I’m not one to easily believe in signs from the other side but a few months ago, my skepticism was tested. At the beginning of an EMDR session (a type of hypnosis therapy used to treat PTSD) in which we were revisiting a traumatic childhood memory of my mom, I was distracted by a dead bird outside my window. The distraction was not so much the ghastly sight of the limp bird, but the larger black bird that was holding the dead bird in a single talon as it precariously perched on the gable of a shed in my backyard. The dead weight of the bird it was clinging onto kept pulling it down the roof, but the black bird refused to let go, repeatedly climbing back up to the top of the shed, dragging the dead bird along the roof.

Then, about halfway through my session, my eyes were drawn to another distraction outside my window—two giant heart-shaped balloons floating up into the sky. As they ascended, one balloon got stuck in the branch of a tree. With the second balloon attached to the first, it was unable to rise any further. The stuck balloon remained lodged in the tree while the free one flailed in the wind. The string that attached the two kept the free balloon tethered to the stuck balloon. The bird eventually flew away, still with the dead bird in its talon. But the two balloons remained attached—one stuck in the tree, the other flailing in the wind—for weeks.

In recent years, I’ve begun to feel the pressure of reaching ten years since my mom died. There is this sense that I shouldn’t still be dragging her dead weight. That I should let her go more easily. That the grief is holding me back in some way.

I’m back in the childhood neighbourhood where every familiar face feels like a mirror reflecting my old and new identities: daughter, caregiver, bereaved. I return to my local pharmacy to pick up my prescription and go to pay at the register instead of my usual self check-out because an employee I remember from my childhood is working the cash. She asked about my gloved hand, I tell her I injured it. “I have a whole new sense of empathy for my mom, she was disabled,” I explain, expecting her to not remember. “Oh yes, I remember helping her with her change,” she responded, much to my surprise. “You two were such a team.”

That night, and every night after, I have visceral nightmares as I sleep on my side of my mom’s bed. The familiarity makes it the most comfortable bed in the world. When I was a kid, I rarely slept in my own bed, my mom was lonely and I adored her, so I stayed up well past my bedtime to watch TV with her. Today, her bed is a cocoon that holds me. It’s also a sink hole that swallows and suffocates me. The nightly descent from consciousness to sleep is not a smooth one, repeatedly interrupted as I’m shaken awake with an overwhelming fear of death. Or a sharp physical sensation. One night, it’s a sudden pain in my chest. A few nights ago, an intense itch on one of my vertebrae. When I go to satisfy the itch, it burns. I rush to the mirror to the horrific sight of an open bleeding sore on my spine. The bed is consuming me. I’ve been wearing a bandage over it ever since—the foundation of my core feels like a jenga tower with a missing block.

In my waking hours, I keep visualizing grief as a hole in the ground. When the hole is first created, it’s obvious. You know to step around it so as to avoid falling in. Over time, the grass grows and the hole remains, but it’s concealed. No longer easily visible to the eye, only you know it exists and that if you’re not careful, you could fall in, disappear into it. Just because you can’t see it, doesn’t mean it’s not there. As time passes and the length of her absence grows, so too does the hole. Missed life markers, missed failures, missed achievements, missed mundane moments—with every absence, the hole grows deeper.

But over time the grief also gets quieter. I can’t tell if this means it’s healing or secretly metastasizing.

What’s scary is not the loss itself, but the monster that can grow in the space between oneself and the loss. Grief itself is not a problem, but the self-destructive mechanisms we use to cope with the unimaginable pain can be.

My skepticism towards supernatural coincidences was tested again a couple weeks ago, in Boynton Canyon, a region known to be an energy vortex. At my wellness resort’s welcome reception, a staff healer explains the higher frequency electro-magnetic energy that has attracted Native Americans here for centuries and I notice the guest sitting across from me looks just like my mom. As we go around the circle introducing ourselves, she breaks down in tears (just like my mom would) as she explains she is here to celebrate her daughter’s 30th birthday, who sits beside her looking annoyed. I long for the hatred and love that radiates between them.

On my last night at the wellness resort, I had a two-hour intuitive massage that turned out to be less massage, and more energy healing. As he assessed my body, and diagnosed my emotional blockages based on what he could feel, I could feel myself holding back tears. I finally broke when he asked me to visualize myself in the mirror and repeat affirmations to my reflection. The sight of myself horrified me.

It was only when I was coincidentally invited to practice the same exercise a week later, back home in my restorative yoga class, that I realized why my own reflection pained me so much. Unlike the first visualization, this one began with picturing someone you love and imagining them happy, healthy and safe from harm. I visualized my mom. Then we were asked to picture ourselves, and imagine extending the same feelings inward. It was so easy to send feelings of love toward my mom, even when she’s no longer here in her physical form, but much harder to send them to myself.

If I spent the second decade of my life learning how to take care of and love my mom, I spent the third learning how to take care of myself. On the surface, this third decade has looked like the best of my life. Yet I would give it all up to be arguing with her everyday and scraping by on her disability income. Even though that life was harder in many ways, I’d give anything to have it back. Because it’s a lot more fulfilling looking after someone else than yourself. And while my mom wasn’t an easy person to love, it still was easier to love her than it is to love myself.

If a decade of grief has taught me anything, it’s that one of grief’s greatest challenges is learning where to channel the energy you directed toward the person you lost; how to transmute that love for the person toward yourself. I’ve figured out the former, but not the latter. Perhaps this is how I’ll spend the next decade: learning how to love myself with as much devotion as I loved her.

Best,

Anna

Published 📝

The Takeout - International Sausages You Need To Try At Least Once

Self-explanatory 🌭

Lonely Planet - How To Plan A Wellness Trip To Seoul

Some travel to experience the beauty of a place, others travel to acquire beauty for themselves. Seoul, South Korea offers both. In 2023, 605,768 travellers visited South Korea for cosmetic procedures. Many of these visitors will spend all their time in cosmetic clinics undergoing treatment and miss out on all Seoul has to offer. “People who come for beauty treatments don’t get to experience the cultural piece,” explains Dr. Eunice Park, the founder of AIREM. The cultural piece Dr. Park refers to is not just tourism attractions, but South Korean beauty and wellness practices, which long predate the rise of K-beauty. From traditional Korean bath houses, known as jjimjilbangs, to top-notch spas to vegetarian Buddhist temple restaurants—the city is teeming with opportunities to find some R&R. I covered the city’s full-range of beauty and wellness offerings, plus where to eat and sleep, in my latest for Lonely Planet.

Reading 📖

💊 The pill that promises to cure grief.

🤳 The thing about memories is you can’t choose which you forget.

📺 Television and dinner, in their infinite repetitions, can quiet the fear of loss, but they cannot actually stop it from occurring.

🌪 First his mother died, then his house got hit by a tornado.

“The universe is indifferent, and that is terrifying, and that is beautiful.” - Ian Bogost.

Personal plug — some of my fave stories I’ve written about grief.

💆🏻♀️ Vogue - Working Through the Layers of My Grief at My Local Asian Spa

👑 Hard Copy - A Royal Fantasy: On Princess Diana, Parasocial Grief and The Digital Footprint We Leave Behind

👩🦯 Self - What Losing My Disabled Mom Taught Me About Ableism

🐅 The Globe And Mail - On Safari in Kenya, I Was Finally Able to Grieve My Mother

💁🏻♀️ Well + Good - I Was Terrified of Being Alone After My Mom Died—Now It’s a Self-Assured Choice I Make Every Day

🪞 Modern Loss - I Lost My Racial Identity When My Mother Died

Watching 📺

My feminist friends hate the Bridget Jones franchise, but I still have a soft spot for it. So when I heard the latest instalment—Mad About The Boy (Prime)—is all about grief, I couldn’t wait to watch. Well actually, I could, because I saved it to watch on the death anniversary this week. I’d heard good things, and still, it exceeded my expectations. The rom-com has corrected some of the critiques of the earlier films, like that Bridget being dependent on a man to save her. It also felt more realistic, as Bridget struggles to maintain her calm as a single mom to two young children. I especially appreciated the way the film treated grief, it was more than a plot device, but didn’t bring down the party. Like the previous Bridget Jones’, this one was filled with swoon-worthy and feel-good moments. The new heart throbs (Leo Woodall and Chiwetel Ejiofor) are great, but Hugh Grant is the real star (is he not aging like a fine wine?).

Listening 🎧

Today’s series of meditations highlights just how difficult it is to articulate what grief feels like. Yet we’ve been using art to process and understand grief for millennia. It felt like a gift that one of my go-to podcasts covered the topic the week before my mom’s death anniversary. Listening, I was reminded of one of my favourite portrayals of grief in recent years—Rachel Bloom’s Death, Let Me Do My Show. I saw the one-woman performance when it ran as an off-broadway production in 2023 but it’s since been released as a Netflix special. As the creator of the hilarious Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Bloom’s deep dive into grief was a surprise to many. But her experience losing her friend Adam Schlesinger to COVID while her newborn was in the NICU called her to make sense (or nonsense) of grief in a musical-meets-stand-up performance.

The podcast episode uses Bloom as an example of how stand-up can be a surprisingly effective setting for exploring the painful topic—from Marc Maron’s From Bleak to Dark to more recently, Sarah Silverman’s PostMortem. My personal favorite of late is Mike Birbiglia’s The Old Man & The Pool.

“Grief is a profoundly isolating experience. It cuts you off from the lost person and the people around you, but it also cuts you off from yourself, there’s a before and an after, the person you were and a person you are now—it’s a point of division in a life. What can art that deals with grief offer for the rest of us? Can it try to be a source of consolation or companionship, or is it enough just to offer a frank accounting of grief, one of the hardest parts of being alive?” - Alexandra Schwartz.

Snacking 🍌

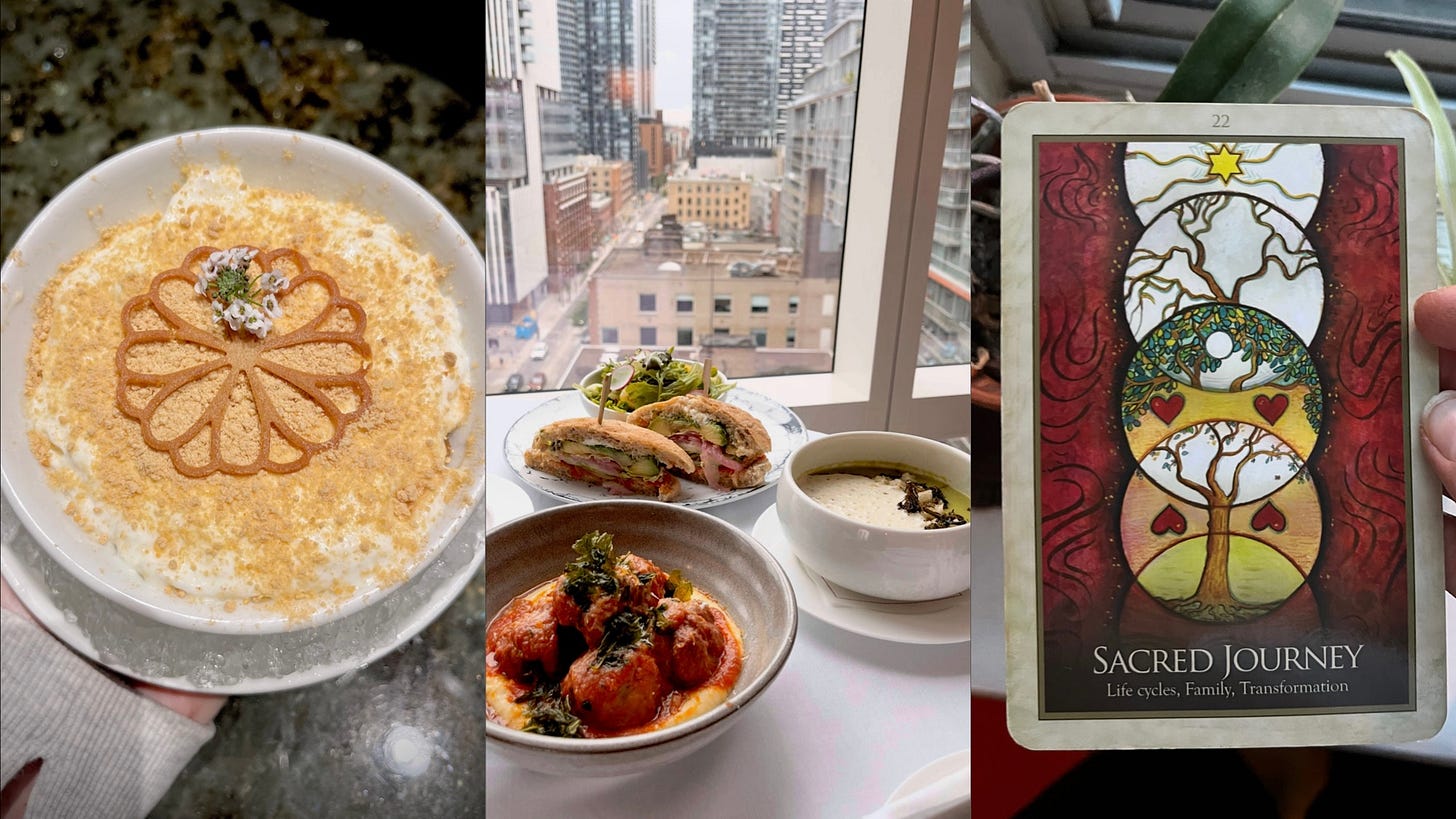

Mom was an anglophile, so I was planning to spend the death anniversary in London. Unfortunately my trip got cancelled so I found myself unexpectedly facing staying in my mom’s and my place on the difficult day. There are a lot of intimidating feels in that apartment so I decided to have an impromptu stay downtown at the Shangri-La to experience their new Eat, Play, Love package. Inspired by the film, every Shangri-La has a different offering for each category with Toronto’s ‘love’ experience centred around a cozy night in, think: a luxurious bath, in-room dining and movie snacks—perfect for a grief anniversary. I knew I made the right choice when I first walked in to hear a woman performing ‘Memory’ from Cats on the piano in the lobby, a song I forgot my mom and I used to sing together. I swear the Shangri-La’s have some of the best bathtub views, and a cinematic thunderstorm on the night of the anniversary made Toronto’s particularly impressive.

The food was the real highlight though as it spurred nostalgia. My babysitter used to make this delicious broccoli soup when I was a kid so I loved the one served at the hotel’s signature restaurant Bosk, laden with Canadian smoked gouda and morel powder. Another recipe I wish I had is my grandpa’s homemade meatballs. Bosk’s are made with Ibérico pork and a thick coating of melted parm atop comforting creamy polenta. I had to order tiramisu in honour of my coffee-addict mom, but my fave dessert was the injeolmi parfait served in the lobby lounge. The milk foam and soy cornflake crunch reminded me of the Korean shaved ice dessert bingsu but the maple mochi made it distinctly Canadian.